Scott B. Guernsey, CERF Research Associate, December 2019

The Shareholder Value of Stakeholder Orientation

Ever since Milton Friedman’s celebrated 1970 article – The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits – the shareholder model of the corporation has commanded widespread acceptance amongst finance academics and practitioners. Under this model, share value maximization provides the exclusive yardstick for managerial performance (Friedman, 1970), while discretion to consider the interests of other stakeholders (e.g., employees, suppliers, customers, creditors, and local communities) is interpreted as enabling managers to rationalize any self-serving action (i.e., “managerial moral hazard”) (Tirole, 2001).

More recently, however, both finance scholars and business leaders have started paying renewed attention to the interests of stakeholders (i.e., “stakeholder orientation”). For example, the article “A Theory of the Stakeholder Corporation”, published in the Econometrica by Michael Magill (University of Southern California), Martine Quinzii (University of California, Davis), and Jean-Charles Rochet (University of Geneva), shows theoretically that firms that exclusively focus on shareholder maximization are more exposed to certain risks that arise from their own investment and production decisions (i.e., “endogenous risks”). And further, that these risks generate negative externalities on stakeholders (e.g., lower wages for employees or higher product prices for consumers), leading them to underinvest in their relationship with the firm and, ultimately, decrease its long-term value. Additionally, institutional investors and CEOs of the largest U.S. corporations seem increasingly willing to accept and even advocate for a corporate model with greater stakeholder orientation (Sorkin, 2018). For instance, on the 19th of August 2019, the Business Roundtable released a trailblazing statement, signed by the nearly 200 CEOs who are its members, redefining the purpose of a corporation and calling for a governance model that benefits not only shareholders but all stakeholders.[1]

Motivated by these developments, in the article “Stakeholder Orientation and Firm Value”, CERF Research Associate Scott Guernsey, and collaborators Martijn Cremers (University of Notre Dame) and Simone Sepe (University of Arizona), study the firm-level implications of increased stakeholder orientation in director decision-making by examining how the enactment of U.S. state-level directors’ duties laws (DDLs) affect shareholder value. DDLs − also known as “corporate constituency statutes” or “stakeholder laws” – increase stakeholder orientation by permitting directors to consider the impact of corporate decisions (such as whether to accept an acquisition offer) on an expanded set of stakeholder interests.

Their main finding is that the enhanced stakeholder orientation enabled by the passage of DDLs results in an increase in the shareholder value of firms incorporated in the adopting states. They show that this value improvement is more pronounced for firms where stakeholder investments are more relevant (e.g., firms that are more reliant on employees, customers, strategic alliance partners, and creditors) or firms that are more engaged in innovative activity (e.g., R&D spending and patenting outputs). The authors also find that, after these laws are passed, employees gain in job security, creditors gain from DDL-firms being more financially sound, and DDL firms increase innovative activity (where stakeholders’ firm-specific investments are key inputs to the firm’s innovation). These benefits, however, tend to be offset in firms with more severe agency problems (e.g., firms with longer tenured CEOs, stronger union influence on management, underutilized assets, and with higher operating expenses or more free cash-flows) where it is more likely that increased director discretion might be abused in the exclusive interest of management.

Overall, their results suggest that shareholders can benefit from greater stakeholder orientation in director decision-making (via DDLs) as it improves the commitment toward stakeholders and reduces contracting costs in many firms, but one size does not fit all.

References mentioned in this post

Friedman, M. 1970. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine. September 13.

Magill, M., M. Quinzii, and J-C. Rochet. 2015. A theory of the stakeholder corporation. Econometrica 83:1685-1725.

Sorkin, A. 2018. BlackRock’s message: Contribute to society, or risk losing our support. New York Times. January 16.

Tirole, J. 2001. Corporate governance. Econometrica 69:1-35.

[1] https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans.

Adeplhe Ekponon, CERF Research Associate, November 2019

Is Firms’ Debt Financing Good for Economic Growth?

In addition to internal funds, firms have two main sources of financing: equity and debt (in general, a mix of both). The latter source of financing comes with tax benefits, and its costs have been historically lower. However, relying heavily on debt financing could increase a firm’s bankruptcy risk. This suggests that there should exist an optimal leverage level (level of debt over the total value of the firm) as suggested by the trade-off theory, i.e., Leland (1994).

There is still some debate as to whether firms should use more debt than they do. According to Miller (1977), taxes are large and certain, whereas bankruptcy is rare and its dead-weight costs are low. Thus, firms should have higher leverage levels than what we observe. Myers (1977) argue that, in the presence of risky debt, equity holders underinvest (debt overhang) because an important fraction of the value generated by these new investments will accrue to debt holders. Debt overhang has also been shown to curb firms’ innovation and investment (see Chava and Roberts, 2008). What about the effects of debt financing at the industry/aggregate level?

Research that follows the trade-off theory treats financing decisions as independent from investment choices, as in Modigliani and Miller (1958), by assuming that the dynamic of the firm’s assets is exogenously given. More generally, very few models consider both financing and investment decisions, particularly when agents are risk averse. Lambrecht and Myers (2017) show that different specifications of managers’ preferences produce different predictions regarding the interactions between financial decisions. With power utility, investment and financing decisions are connected, but with exponential utility, managers separate investment from financing decisions. In both cases, managers underinvest because of risk aversion, confirming the debt overhang phenomenon.

A recent study by Geelen, Hajda, and Morellec (2019) shows that even if debt financing can have a negative effect on innovation and investment at the firm level, it also stimulates entry of new firms in the capital markets, thereby fostering innovation and growth at the aggregate level. What makes this new finding important? Recent productivity growth and job creation are the handiwork of start-ups and tech companies, particularly big tech. However, these firms heavily rely on R&D investments, which are now higher than CAPEX at the aggregate level for public firms (Doidge, Kahle, Karolyi, and Stulz, 2018). Debt is a key source of financing for large and small firms as well as for start-ups (Robb and Robinson, 2014).

To capture these empirical observations, Geelen, Hajda, and Morellec (2019) developed a Schumpeterian growth model (innovation makes existing products obsolete) in which firms’ dynamic R&D, investment, and financing choices are jointly and endogenously determined. The paper shows that although debt financing hampers investment at the firm level (debt overhang), it increases aggregate investment by stimulating creative destruction and entry of new firms.

References mentioned in this post

Chava, S. and Roberts M. R. (2008) "How does Financing Impact Investment? The Role of Debt Covenants." Journal of Finance, 63: 2085-2121

Doidge, C., Kahle, K. M., Karolyi, G. A. and Stulz R. M. (2018) “Eclipse of the Public Corporation or Eclipse of the Public Markets?” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 30: 8-16

Geelen, Hajda, and Morellec (2019) “Debt, Innovation, and Growth.” Working Paper, EPFL

Lambrecht, B. M. and Myers, S. C. (2017) “The Dynamics of Investment, Payout and Debt.” Journal of Financial Economics 89: 209–231

Robb, M., and Robinson, D. T. (2014) “The capital structure decisions of new firms.” Review of Financial Studies 27: 153-179

Oğuzhan Karakaş, CERF Fellow, October 2019

To Vote, or Not to Vote, That is the Question

With the advent of the financial engineering and technology, the fabric of the financial securities is changing. While this change has certain advantages such as bringing the costs down, it also has unintended consequences such as impairing the associated voting rights in the securities. A potential reason underlying this issue is the oversight in the design of the new financial securities and the underlying regulations: in contrast with the cash flow rights, the non-cash-flow-related contractual rights of the securities, including the right to vote, or the right to sue, tend to be overlooked.

Contemporaneously, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has been inquiring and debating about the “proxy plumbing” – extensive problems, ranging from over-voting to under-voting, associated with the complex, dated, and inefficient infrastructure supporting the proxy voting system. A recent recommendation of the SEC Investor Advisory Committee on proxy plumbing argues that SEC intervention is necessary for the overhaul of the system.[1]

In the article “Phantom of the Opera: ETF Shorting and Shareholder Voting”, CERF Fellow Oğuzhan Karakaş and research collaborators Richard Evans (University of Virginia), Rabih Moussawi (Villanova University), and Michael Young (University of Virginia), find that short-selling of Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) lead to “phantom shares” of the underlying that are not voted. This unintended consequence is due to the underlying shares held as collateral or a hedge by the securities lenders or authorized participants/broker-dealers. The authors show that phantom shares (i) are costly, since they do not convey voting rights to the ETF owners, but are sold at the full price of share, which reflects both cash flow rights and voting rights; (ii) create inefficiencies within the voting process by leading to under-voting; (iii) are positively related to voting premium, particularly during the contentious votes; and (iv) are associated with poor governance such as value-reducing acquisitions.

Regulatory concerns regarding the above-mentioned findings would arguably be even more pronounced during times market is bearish and/or when the corporate votes are very valuable. A solution could be to incorporate the distributed ledger technology (commonly known as “blockchain”) into the proxy system, as also discussed at the recommendation of the SEC Investor Advisory Committee on proxy plumbing.

References mentioned in this post

- Evans, R.B., O. Karakaş, R. Moussawi, and M. Young. 2019. Phantom of the Opera: ETF Shorting and Shareholder Voting. Working Paper, University of Virginia, University of Cambridge and Villanova University.

[1] https://www.sec.gov/spotlight/investor-advisory-committee-2012/iac-recommendation-proxy-plumbing.pdf

Scott B. Guernsey, CERF Research Associate, September 2019

FinTech Disruption: Is it Good or Bad for Consumers?

Financial technology (“FinTech”) is a rapidly growing industry that applies recent digital innovations and technology-enabled business model innovations to financial services. A common example is its application of smartphone technologies to banking. For instance, from the convenience of a mobile phone, FinTech consumers can access depository accounts, transfer funds, request loans, and pay monthly bills. Correspondingly, the emergence of the FinTech industry has expanded the accessibility of many financial services to the general public.

Recent regulation in the EU (the Second Payment Services Directive – PSD2) and the UK (the Open Banking initiative) suggests that policy makers generally regard FinTech’s entrance into the financial services industry favourably.[1] Mandated by these respective legislative actions, traditional banks must release data on their customers’ accounts to authorized FinTech firms, with the aim of opening “up payment markets”, “leading to more competition, greater choice and better prices for consumers” (Summary of Directive (EU) 2015/2366 on EU-wide payment services). But is the competition/disruption created by FinTech firms in financial services’ markets always in the interests of consumers? And what role does the portability of data – as required by the PSD2 and the Open Banking initiative – play in these markets?

A recent research article presented at this year’s Cambridge Corporate Finance Theory Symposium by Professor Uday Rajan (University of Michigan) demonstrates the complex effects that may arise when a FinTech entrant and an incumbent bank compete in the market for payments processing. The paper begins by underscoring two important functions that a bank provides to consumers: (i) it processes their everyday payments (e.g., reoccurring bills), and (ii) it offers them loans when requested. Intuitively, these two financial services are interconnected as the transaction data created from processing payments enables the bank to be informed about their consumers’ credit quality. This information externality makes the bank better off and incentivizes it to bundle payment services and consumer loans. More surprisingly, the paper finds that consumers can also gain from the bank having their information as more creditworthy consumers are offered better interest rates on their loans.

From this starting point, Professor Rajan (and co-authors, Professors Christine Parlour and Haoxiang Zhu) then show that competition from FinTech firms, which act purely as payment processors, can disrupt the bank’s information flow. Consequently, the bank loses market share, consumer information, and becomes less profitable. Additionally, consumers that might need a loan can also suffer from this lost information. Moreover, the entrance of a FinTech firm can either decrease or, quite surprisingly, increase the price the bank charges for its payment services. This latter instance occurs if the bank opts to focus its payment business on the population of consumers that are more reliant on (or have a greater affinity for) brick-and-mortar banks, and thus are more tolerant of higher prices. Conversely, the consumer population that is more technologically sophisticated and willing to use FinTech services experience the greatest gains as their cost for payment services are reduced by the added competition.

The authors then apply their model to a world in which consumers are given complete ownership and portability of their payment data. They show that this policy effectively unbundles a bank’s payment services from its bank loans, which in turn has different ramifications for different consumers. On the one hand, a certain subset of the consumer population that is more technologically sophisticated and less reliant on a traditional banking relationship is made better off via more choice and lower prices. On the other hand, consumers that have a greater affinity for banks and that are less technologically sophisticated can be hurt by policies that mandate portability of their data because the bank will exploit this smaller group of bank-reliant consumers, charging a higher price for its payment services. These key results underline both the good and bad of FinTech disruption and the likely heterogeneous effects of PSD2 and the Open Banking initiative on consumer welfare.

[1] See Directive 2015/2366/EU (25 November 2015), and the United Kingdom Competition and Markets Authority’s (CMA) retail banking market investigation report (9 August 2016).

Adeplhe Ekponon, CERF Research Associate, August 2019

Agency Conflicts and Costs of Equity

The agency problem, in the context of separation in ownership (shareholders or the principals) and control (managers or the agents), is one of the most important issues in corporate finance.

This separation may induce conflicts of interest inherent in the kind of relationship where an agent is expected to work in the best interests of a principal. In the case of a company, these conflicts of interest arise when executives, or more generally insiders which could include controlling shareholders, favour their interests at the expense of the company's goals.

There are various manifestations of this behaviour. Managers may appropriate part of the profits, sell the firm’s output or assets at under the fair value to their own business, divert profitable growth options, or recruit unqualified relatives at high positions. See Jensen and Meckling (1976), La Porta et al. (2000, 2002), and Lambrecht and Myers (2008).

Impacts of self-interested management on corporate choices and asset prices have been extensively described by several theoretical and empirical works. They document that entrenched managers tend to underinvest and choose lower leverage. In response, shareholders may force them to increase leverage, because coupon payment reduces the firm’s free cash flows which limits the amount available for cash diversion. Therefore, debt can be used as a tool to discipline managers. Entrenched managers can also resist hostile takeovers and lead shareholders to push for the adoption of more provisions that reduce their own rights.

All these frictions reduce not only profits but also operational efficiencies and affect equity prices and volatility. To measure the impact of agency costs on equity prices, Gompers, Ishii, and Metrick (2003) and Bebchuk, Cohen, and Ferrell (2009) have constructed indexes, G-index and E-index respectively, to measure for the balance of power between shareholders and managers. High index levels (extensive management power) translate into high agency costs. They document that increases in these indexes level are associated with economically significant reductions in firm value, profits and equity price during the 1990s.

Most theoretical papers that study the impacts of agency conflicts on asset prices do not emphasize on its influence on costs of equity. Empirical papers, however, only focus on the level of the severity of the conflict.

A working paper by CERF Research Associate, Adelphe Ekponon, proposes a theoretical approach and provides empirical evidence that time-series fluctuations of this conflict have as well the potential to explain cross-sectional differences in equity prices. Specifically, the difference in average index values in bad times compared to normal periods is positively correlated to the cost of equity, even after controlling for preeminent markets factors. Data are from 1990 to 2006.

The most important economic implications of this result are twofold: firms with countercyclical governance policy (better governance in bad times) have a lower cost of equity. Changes in governance practices in bad vs. good times is a pricing factor for stocks.

Interestingly, the paper shows that these results are closely linked to managers-shareholders conflicts, as it documents a U-shape relationship between changes in G-index and cost of equity (too many restrictions in bad times create conflicts and impediment managers ability to run the company efficiently), while this relationship is linear for the E-index. This latter index has been constructed on a subset of the G-index that focuses on managerial entrenchment.

References mentioned in this post

Bebchuk, L., Cohen, A. and Ferrell, A. (2009), What matters in corporate governance?, Review

of Financial Studies 22(2), 783–827.

Gompers, P., Ishii, J. and Metrick, A. (2003), Corporate governance and equity prices, Quarterly

Journal of Economics 118(1), 107–156.

Jensen, M. C. and Meckling, W. H. (1976), Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency

costs and ownership structure, Journal of Financial Economics 3(4), 305–360.

Lambrecht, B. M. and Myers, S. C. (2008), Debt and managerial rents in a real-options model

of the firm, Journal of Financial Economics 89(2), 209–231.

LaPorta, R., de Silanes, F. L., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. (2000), Investor protection and

corporate governance, Journal of Financial Economics 58(1-2), 3–27.

LaPorta, R., de Silanes, F. L., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. (2002), Investor protection and

corporate valuation, Journal of Finance 57(3), 1147–170.

Dr. Hui Xu, CERF Research Associate, July 2019

What determines the cryptocurrency’s excepted return?

Since the emergence of the cryptocurrencies, they have quickly become the focus of asset managers. Although many ongoing debates about cryptocurrencies still remain to be solved, e.g. whether their value can be justified, their relationship with the fiat money endorsed by the central banks, they do offer an alternative opportunity for the investors to diversify their portfolios. Yet before constructing a portfolio that subsumes cryptocurrencies, a question has yet to be answered: what is their risk and return profile and what are the determinants?

Since stocks markets are well developed and thoroughly studied, it is only intuitive to look at whether the factors that successfully account for stocks markets can also apply to the cryptocurrencies market. Although shares and cryptocurrencies are fundamentally different, they do share quite amount of similarities. Especially, some cryptocurrencies (digital tokens) represent the claim to the issuer. Eugene F. Fama and Kenneth R. French in 1992 found that size risk and value risk can account for the stock return in addition to the well-known Beta, based on the evidence that value and small-cap stocks outperform market on a regular basis. Mark Carhart augmented the three-factor model by adding a momentum factor that describes the tendency for the stock price to continue rising if it is going up and to continue declining if it is going down.

A recent NBER Working Paper by Aleh Tsyvinski et. al. tested the idea and showed that most of the powerful explanatory factors in the stock market, namely the beta, size and momentum, are also powerful to capture the cross-sectional expected returns of cryptocurrencies. Since the advent of cryptocurrencies, many have studied the expected returns and many explanatory factors have been suggested. Interestingly, they showed that all of the excess returns generated by the trading strategies that previous studies implied, in fact, can be accounted for by the cryptocurrency three-factor model.

A further inquiry is whether there exists a “twin” value factor in the cryptocurrency market, why the size and momentum factors are so mysteriously powerful and whether they affect the cryptocurrency returns the same way as they do to the stock returns? One thing for sure is that as the cryptocurrency market continue to burgeon, all these questions will be answered eventually.

Shadow Pills and Visible Value

By: Scott B. Guernsey, CERF Research Associate, June 2019

The “poison pill” (formally known as a “shareholder rights plan”) has a long and contentious history in the United States as a tactic to deter takeovers.[1] While details can vary across different implementations, the key defensive mechanism of the pill provides existing shareholders with stock purchase rights that entitle them to acquire newly issued shares at a substantial discount in the “trigger” event that a hostile bidder obtains more than a pre-specified percentage of the company’s outstanding shares (e.g., 10-15%).[2] As a result, poison pills permit a firm’s board of directors the ability to substantially dilute the ownership stake of a hostile bidder, de facto giving the board veto power over any hostile acquisition.

Correspondingly, law and finance scholars generally agree that the poison pill is perhaps the most powerful anti-takeover defense (e.g., Malatesta and Walkling 1988; Ryngaert 1988; Comment and Schwert 1995; Coates 2000; Cremers and Ferrell 2014). However, whether a firm’s managers use the poison pill to the benefit or detriment of its shareholders is the subject of an enduring debate in both the corporate finance literature and in U.S.’ state courts.

Prior empirical studies have attempted to investigate the value implications of a firm’s decision to employ a poison pill as a strategy to deter takeovers. While earlier findings were mixed, over the past decade most studies have found that the adoption of a pill is negatively associated with firm value (e.g., Bebchuk, Cohen and Ferrell 2009; Cuñat, Gine, and Guadalupe 2012; Cremers and Ferrell 2014). Unfortunately, however, this result is challenging to interpret, as the choice to adopt a pill is endogenous – meaning, for example, that the finding might imply that a firm was losing value and decided to adopt a pill in response rather than the conclusion that the adoption of the pill led to lowered firm value. Adding to the difficulty of researchers, since poison pills can be unilaterally adopted by a firm’s board of directors, even firms that do not currently have a poison pill in place still have the right to adopt a pill at any time – this right is termed by scholars as a “shadow pill” (Coates 2000).

In the article “Shadow Pills and Long-Term Firm Value”, CERF Research Associate Scott Guernsey, and research collaborators Martijn Cremers (University of Notre Dame), Lubomir Litov (University of Oklahoma), and Simone Sepe (University of Arizona), contribute to the debate on the value implications of the poison pill by shifting the focus from “visible” (or realized) pills to shadow pills – that is, studying the effect that arises from the right to adopt a poison pill rather than its actual adoption. To do this empirically, the study’s tests focus on U.S. state-level poison pill laws (“PPLs”) – enacted by 35 states between 1986 and 2009 – which legally validated the use of the pill, hence strengthening these firms’ shadow pill.

Using the staggered enactments of PPLs by different states in different years, the authors find that firms incorporated in states with a stronger shadow pill experience significant increases in firm value, and especially for firms with stronger stakeholder relationships (e.g., with a large customer or in a strategic alliance) and more engaged in innovation (e.g., R&D investments or with patents). Additionally, the study confirms the prior literature’s results on a negative correlation between firm value and actual pill adoption.

Overall, the authors’ findings suggest that a stronger shadow pill can benefit certain firms’ shareholders, even if a visible pill does not, indicating that for these firms the right to adopt a pill could serve as a function of good corporate governance by credibly signaling a firm’s bond toward more stable stakeholder relationships and/or longer-term investment projects through its commitment against potential disruptions from short-term shareholder interference via the takeover market.

References mentioned in this post

Bebchuk, L., A. Cohen, and A. Ferrell. 2008. What matters in corporate governance?. Review of Financial Studies 22:783-827.

Coates IV, J.C. 2000. Takeover defenses in the shadow of the pill: A critique of the scientific evidence. Texas Law Review 79:271-382.

Comment, R., and G.W. Schwert. 1995. Poison or placebo? Evidence on the deterrence and wealth effects of modern antitakeover measures. Journal of Financial Economics 39:3-43.

Cremers, M., and A. Ferrell. 2014. Thirty years of shareholder rights and firm value. Journal of Finance 69:1167-96.

Cuñat, V., M. Gine, and M. Guadalupe. 2012. The vote is cast: The effect of corporate governance on shareholder value. Journal of Finance 67:1943-77.

Malatesta, P.H., and R.A. Walkling. 1988. Poison pill securities: Stockholder wealth, profitability, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 20:347-76.

Ryngaert, M. 1988. The effect of poison pill securities on shareholder wealth. Journal of Financial Economics 20:377-417.

Slaughter and May. 2010. A guide to takeovers in the United Kingdom. http://www.slaughterandmay.com/media/39320/a_guide_to_takeovers_in_the_uk_mar_2010.pdf

[1] The use of the poison pill is not permitted in the U.K. because: (i) it is viewed as a breach of fiduciary duty, and (ii) it is disallowed by General Principle 3 and Rule 21 of the City Code (Slaughter and May 2010).

[2] This describes the “flip-in” poison pill which has become largely majoritarian in the U.S.; for other methods see: “preferred stock plans,” “flip-over” poison pills, “back-end rights plans,” “golden handcuffs,” and “voting plans.”

Adelphe Ekponon, CERF Research Associate, May 2019

A corporate finance model for Cryptocurrencies

After the credit crunch of 2009, you may have heard of Bitcoin or cryptocurrencies in general. Bitcoin and altcoins (terminology used to refer to all other cryptocurrencies) are digital currencies built on distributed ledger technologies such as Blockchain and so are not regulated by a central authority. Whether cryptocurrencies are perceived as currencies by authorities, or treated as financial assets by investor and regulators, or whether they can be used as security token or utility token, it is clear the digital currencies’ market is a small but growing market’ as commented by Christopher Woolard, executive director of Strategy and Competition at the FCA (UK Financial Conduct Authority) [1].

From Bitcoin, invented by the so-called Shatoshi Nakomoto, more than 2000 other altcoins have been created for various purposes [2]. The market capitalization for the largest 100 cryptocurrencies has increased from 1.5 Billion in 2013 to 250 Billion in May 2019, with a peak of 795 Billion in January 2018. With such an interest from not only individual consumers but also Business users, authorities in countries such the UK, France, Switzerland, South Korea, the United States and others have initiated regulatory sandboxes either to educate consumers (UK, Guidance) or to create high level government task forces to investigate the technology and regulatory implications.

Authorities around the world, including governments and central banks, often remain skeptical about the digital currencies, rightfully because many questions either on the scalability of the underlying technology [3] or concerning the nature of the crypto assets are subject to investigation and clarification prior to potential wider adoption of the technology.

As mentioned above, the price of cryptoassets on exchange places shows extremely high volatility compared to for instance the equity market. Authorities and trading exchange often warn that prices can fall to zero overnight. This raises the questions as to whether any cryptoasset has a fundamental value which can sustain its market price or whether crypto prices follow a completely different pricing model which need to be investigated.

In ongoing work, CERF Research Associate A. Ekponon and K. Assamoi (Liquidity analyst at MUFG Securities) propose a corporate finance model for the pricing of cryptocurrencies.

First, they model the scale level of a cryptofirm, e.g. Bitcoin or Ethereum, following Bhambhwani et al (2019) and Hayes (2015). This scale is assumed to be constant but may change (infrequently) up or down over time following fundamentals. Cryptofirms remain to be clarified in term of investment. This paper takes the view that a cryptocurrency is classified as a financial asset [4].

If so the overall activity around a cryptofirm could be transcribed in a usual firm setting. Fundamental values represent initial cash-flow level whenever the firm changes scale. Miners, which work consist in validating these peer-to-peer transactions, represent labour. Successful crypto mining produces new bitcoins to miners (block fees) and improves the trust in and security of the technology, making crypto-firm more valuable. Validating transactions are also rewarded by bitcoin users through transactions fees. Rewards to miners constitute wages. Computation costs incurred by miners are also counted for.

Second, this article assumes that a cryptocurrency corresponds to equity for the firm and its cash-flow evolves around its fundamental levels following standard Brownian motions.

Third, the optimal level of firm fundamentals, among which, the difficulty in the validation of operations, the rate of unit production, the cryptologic algorithm employed or the aggregate computing power, and also cryptocurrency price are derived by using methods from dynamic models of corporate finance (See Strebulaev, 2007).

The paper findings are tested with daily prices of more than 100 cryptocurrencies among the most actively traded. Results from the model implications and empirical tests will be detailed in a future blog.

References mentioned in this post

Bhambhwani, S., Delikouras, S. and Korniotis, G. M., Do Fundamentals Drive Cryptocurrency Prices? (May 9, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3342842.

Hayes, Adam, What Factors Give Cryptocurrencies Their Value: An Empirical Analysis (March 16, 2015). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2579445.

Strebulaev, I. A., 2007, Do tests of capital structure mean what they say? Journal of Finance

62, 1747–1787.

[1] https://www.fca.org.uk/news/press-releases/fca-consults-cryptoassets-guidance

[2] https://coinmarketcap.com/all/views/all/

[3] EU Blockchain Observatory, Overview and Guiding on Blockchain Scalability and Security Topics, Working Group Blockchain/ICO, 2018, recommendations on future regulations.

[4] 2nd Global Cryptoasset Benmarking Study, Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance

Thies Lindenthal, CERF Fellow, Land Economy, May 2019

Machine Learning, Building Vintage and Property Values

Sometimes, all you need is a bit of luck. Erik Johnson (University of Alabama) and I had explored a new way to integrate images from Google Street View as additional input to automatic real estate valuation systems. Writing up the working paper[1], we were looking for relevant policy implications beyond the mundane goal of boosting price prediction accuracy. We struggled. But then the head of UK’s Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission went on the record, claiming that Britain’s housing supply constraints will evaporate if only developers build “as our Georgian and Victorian forebearers built [. . . ] All objections to new building would slip away in the sheer relief of the public”[2]. The research we had done enabled us to put this refreshing view to the test (and to add a policy dimension to the paper).

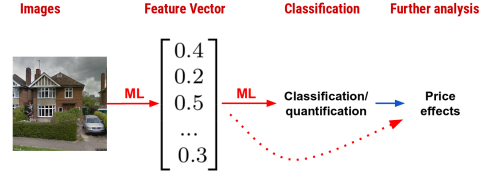

In a nutshell, our approach automates a process that those of us who have been trying to find a place to rent or buy are surely familiar with: To learn more about a potentially interesting home, one looks it up on Google Street View and tries to infer additional information from the images of the building itself and also get a feeling for the neighbourhood. Street level images are a rich data source, answering many questions such as: How big is the property and garden? How old is it? Is the exterior well-kept? Has the house charm? Is it’s architecture pleasing to the subjective eye? And much more. The challenge is to automatically identify the correct building on Street View, take the best possible picture and to classify the property in several dimensions using computer vision (CV) and machine learning (ML) techniques.

Extracting images of individual buildings from Street View was a bigger challenge than expected. Google’s address information are often relatively broad guesses in the UK. Try finding e.g. “84 Vinery Road, Cambridge, CB1 3DT” on Street View to experience the problem yourself. Based on exact maps from the Ordnance Survey we solve this more technical first step and collect front images of practically all residential homes in Cambridge.

In the ML application, we initially focus on training a classifier for the vintage of buildings. According to colleagues from the architecture department, local houses can be classified into seven broad eras: Georgian (c1714–1837) houses feature key characteristics such as sash windows, fan lights above doors, the use of stucco on facades, often wrought work grilles, railings etc. In the Early Victorian era (c1837–c1870s), a growing taste for individualized embellishment led to the development of elaborate features such as carved barge boards or finials. The development of sheet glass led to sash windows becoming more affordable, and, increasingly, wider. In the Late Victorian era (c1870s–1901), bay windows became more and more widespread, and increasingly substantial. Edwardian architecture (1901-1910) tends to be less ornate than late Victorian architecture. The Interwar period (1918–1939) saw the cost of building construction fall, amidst a drive to provide better housing for the working classes. New housing types were being favoured. The Postwar (1950-1980) era continued on this path, with an embrace of high-rise as well as low rise housing. Facades vary greatly between brick, tiling, pebbledash and render. Our cut-off year for our Contemporary era to begin is 1980. Revival are contemporary buildings trying to emulate historical architecture. It should be self-evident, that the sheer amount of details and variations defies a simplistic classification approach.

We suggest a transfer learning approach in which the images are first translated into high-dimensional feature vectors using an existing CV model (Inception V3[3]). A classifier is then trained to categorise the buildings into vintages, based on the feature vectors (Softmax). An true innovation of our approach is that we include information on neighbouring buildings into the classification, exploiting spatial dependency in building vintages.

Note: Feature vectors generated by Inception V3 have 2,048 dimensions which favours a ML approach (in contrast to e.g. multinomial logit regressions) in the classification step.

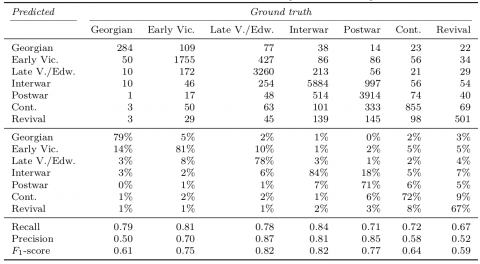

Two final-year architectural students classified a large sub-sample of approximately 25,000 images from our data set of Cambridge houses. This is a much larger sample than ultimately needed. In our case, each category requires less than 250 samples to reach almost fully diminished training accuracy for additional observations. We greatly exceed this number so that we can compare the out-of-sample convolutional neural network predictions to the groundtruth as assigned by the experts. This allows us to examine the power and size of the assignment tests. In addition having both human and machine classification for a large sample of the data allows for a robustness checks on the machine comparisons. The accuracy of the automatic prediction is high (Table 1): A machine can relatively reliably tell different building vintages apart, even Revival styles are detected. All comes at modest cost, classifying the universe of buildings in Cambridge takes only seconds on a contemporary laptop.

Table 1: Confusion matrix – Predicted vintage vs. ground truth

Note: Recall is the share of buildings from a ground truth category being predicted correctly (diagonal in mid panel) and Precision is the share of buildings predicted to belong to a category that are indeed from that category. The F1-score is the harmonious mean of Precision and Recall: F1-score = 2 Recall * Precision / (Recall + Precision)

Coming back to the claim made by Building Better, Building Beautiful on historic aesthetics being valued by the people: If that were true, buyers should prefer revival architecture over more contemporary designs. Also, buildings with adjacent buildings in historic or revival appearance should command a price premium. How hard we look, we cannot find any evidence for such a preference in real transaction data. After controlling for a house’s location, size and quality, modern designs are as sought after as replicas of old styles. Not surprising, reviving the good old times will not solve the housing shortage.

We have to speed up the publication of our paper as much as we can, or we risk losing our policy relevance again: The chairman of the helpful government commission has been fired in the meantime – for reasons not related to our research, though.

[1] https://github.com/thies/paper-uk-vintages/blob/master/text/manuscript_assa.pdf

[2] Scruton, Roger. 2018. “The Fabric of the City.” Colin Amery Memorial Lecture. Policy Exchange.

https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/The-Fabric-of-the-City.pdf.

[3] Szegedy, Christian, Vincent Vanhoucke, Sergey Ioffe, Jonathon Shlens, and Zbigniew Wojna. 2015. “Rethink-

ing the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision.” https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.308.

Scott B. Guernsey, CERF Research Associate, March 2019

As described in the article “The Choice between Formal and Informal Intellectual Property: A Review”, published in the Journal of Economic Literature by Bronwyn Hall (University of California, Berkeley), Christian Helmers (Santa Clara University), Mark Rogers (Oxford University), and Vania Sena (University of Essex), the UK Community Innovation Survey suggests that most UK-based companies consider trade secrets one of the most effective mechanisms to protect their intellectual property. Further, the recent passing of the “Trade Secrets (Enforcement, etc) Regulations 2018” (SI 2018 No. 597) act by Parliament indicates that UK policymakers are also concerned with protecting domestic trade secrets.

Loosely defined, trade secrets are configurations of closely held, confidential information (e.g., devices, formulas, methods, processes, programs, techniques, etc.), which are used in a firm’s operations, are not easily ascertainable by outside parties, and have commercial value for the holder because it is secret. Common examples include detailed information about a firm’s customer contact and price lists, computer algorithms, cost information, and business plans for future products and services, among others.[1] Although, despite the simplicity and straightforwardness of these examples, the opaque and intangible nature of trade secrets makes it challenging for investors to appropriately assess the risk profiles and fundamental values of companies more reliant on secrecy.

As explained in the legal article “Bankruptcy in the Age of ‘Intangibility’: The Bankruptcies of Knowledge Companies” by Mathieu Kohmann (Harvard Law School), the difficulty in assessing the risk and value of trade secrets is even more alarming for creditors of financially distressed or defaulted firms. For one, trade secrets cannot generally be collateralized in debt contracts. And second, even if the secrets were pledgeable to lenders, they do not have active secondary markets, making their redeployability and liquidation in bankruptcy costly and largely infeasible. Prior theoretical work in the financial economics literature, further suggests that firms composed primarily of intangible assets (e.g., trade secrets) sustain less debt financing because these types of assets decrease the value that can be captured by lenders in the event of default.[2]

Motivated by the increasing importance of secrecy for firms and governments, and the corresponding difficulties borne by creditors of these types of firms, in the article “Keeping Secrets from Creditors: The Uniform Trade Secrets Act and Financial Leverage”, CERF Research Associate Scott Guernsey, and research collaborators Kose John (New York University) and Lubomir Litov (University of Oklahoma), examine the impact of stronger trade secrets protection on firms’ capital structure decision-making.

To empirically analyze the relationship between trade secrets protection and financial leverage, Dr. Guernsey focuses his study on the adoption of the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA) by 46 U.S. states from 1980 to 2013. The UTSA, much like the recent “Trade Secrets (Enforcement, etc) Regulations 2018” in the UK, improves the protection of trade secrets by codifying existing common law, standardizing its legal definition, detailing what constitutes illegal misappropriation (e.g., bribery, theft, espionage), and clarifying the rights and remedies of victimized firms (e.g., injunctive relief, damages, reasonable royalties). Using the staggered adoptions of the UTSA by different states in different years, the authors find that firms located in states with enhanced trade secrets protection reduce (increase) their use of debt (equity) financing, compared to firms operating in the same U.S. Census region[3] and sharing similar industry trends but headquartered in states without the laws’ protection.

Next, Dr. Guernsey explores a possible economic explanation for the reduction in debt ratios experienced by firms located in states with the UTSA. The authors find evidence for the “asset pledgeability hypothesis” which conjectures that stronger trade secrets protection incentivizes firms to increase their reliance on secrecy (and away from patents), which, correspondingly, increases intangibility, leading to enhanced contracting problems with creditors – since such assets are more difficult to redeploy and liquidate in secondary markets –, ultimately, leading to less borrowing. For instance, relative to industry rivals operating in similar geographical regions, firms located in UTSA enacting states increase their investments in intangible assets and research and development (R&D), and experience decreases in the liquidation value of their assets and in their reliance on patents.

Overall, Dr. Guernsey’s findings provide important insights into how greater reliance on trade secrets affects corporate leverage decisions – indicating that companies with stronger protection choose to keep their secrets from creditors.

References mentioned in this post

Hall, B., C. Helmers, M. Rogers, and V. Sena. 2014. The choice between formal and informal intellectual property: A review. Journal of Economic Literature 52: 375-423.

Kohmann, M. 2017. Bankruptcy in the age of “intangibility”: The bankruptcies of knowledge companies. Unpublished Working Paper, Harvard Law School.

Long, M.S., and Malitz, I.B. 1985. Investment patterns and financial leverage. In: Corporate capital structures in the United States. University of Chicago Press, Illinois, pp. 325-352.

Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R.W. 1992. Liquidation values and debt capacity: A market equilibrium approach. Journal of Finance 47: 1343-1366.

Williamson, O.E. 1988. Corporate finance and corporate governance. Journal of Finance 43: 567-591.

[1] For instance, the Coca-Cola soft drink recipe, Google’s search algorithm, McDonald’s Big Mac special sauce, and the New York Times Bestseller List are among the most famous examples of trade secrets.

[2] For example, see, Long and Malitz (1985), Williamson (1988), and Shleifer and Vishny (1992).

[3] The U.S. Census Bureau groups states into four census regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West.

Dr.Adelphe Ekponon, CERF Research Associate, February 2019

Long-term Economic Outlook and Equity Prices

The very first asset pricing models (also called Capital Asset Pricing Models or CAPM) have postulated that the only risk that is needed to characterize a stock price is the contemporaneous correlation between the firm and the market portfolio returns. This implies that investors pay much more attention to information about the current economic conditions. Yet models that only incorporate this correlation risk tend to be unable to capture the dynamic of equity returns. The empirical asset pricing model proposed by Fama and French (1992) demonstrate that CAPM has no explanatory power to explain the cross-section of average stocks returns on portfolios sorted by size and book-to-market equity ratios.

An important trend of the literature has developed models to improve pricing performances of the CAPM via a consumption-based approach, CCAPM. The main innovation of CCAPM models lies in the introduction of macroeconomic conditions into asset pricing. According to these models, risk premia should be proportional to consumption beta (correlation between the firm's profit and consumption). However, this line of CCAPM models are known to produce very little level of equity risk premium, less than 1% for reasonable levels of risk aversion. These models are also rejected by several empirical tests.

Since then, two new features have been introduced in asset pricing. The first comes from the observation by Hamilton (1989) that shocks to the US economic growth are not i.i.d. as growth rates may also shift from periods of high to low levels. Secondly, a new class of utility functions introduced by Epstein and Zin (1989), allows to isolate, the aversion to future economic uncertainty from that of the current correlation risk.

Bansal and Yaron (2004) and recent papers have successfully developed consumption-based models in which the representative agent has Epstein-Zin type of preferences. These models pave the way to disentangle the impact of long-run vs. current correlation risks in stock prices. Additionally, they generate reasonable levels of equity risk premium and are able to explain some key asset pricing phenomena. Here, long-run risk (LRR) captures the unforecastable and persistent nature of future economic conditions and has two components, expected growth rate and volatility.

Constructed on this last trend of papers, Dorion, Ekponon, and Jeanneret (2019) propose a consumption-based structural approach, with endogenous default and debt policies, that allows investigating both long-run and correlation risks individually and in tandem. This is the first study to isolate and quantify, conditional on the state of economy, the impact of LRR in equity prices.

They found an average risk premium of 1% in expansion against 6% in recession. The paper also predicts that long-run risk represents about three-quarters of this risk premium and that its impact is countercyclical, being more than 90% in recession. To reduce the impact of LRR, managers lessen the optimal amount of debt to issue and lower the default barrier. Despite these adjustments, LRR still governs equity premium leading to the above predictions.

Using U.S. stocks prices, consumption growth (correlation risk), and expected economic growth rate and volatility (long-run risk), over the period from 1952 to 2016, this study confirms that LRR is priced in U.S. firms, particularly in bad times. These data show that the compensation for LRR represents around 70% of excess returns in a zero-investment portfolio, consisting in shorting stocks which returns have a low correlation with expected growth rates (or high correlation with expected growth volatilities) and buying stocks with high correlation with expected growth rates (or low correlation with expected growth volatilities). These results imply that LRR is a priced risk factor for equity.

Hence, investors are compensated for trading/holding stocks based on their sensitivity to future economic conditions. This result provides a strong evidence that long-run economic outlook is an important driver of equity premium at the cross section.

References mentioned in this post

Bansal, R. and Yaron, A. (2004), Risks for the long run: A potential resolution of asset pricing puzzles, Journal of Finance 59(4), 1481-1509.

Epstein, L. G. and Zin, S. E. (1989), Substitution, risk aversion, and the temporal behavior of consumption and asset returns: A theoretical framework, Econometrica 57(4), 937-69.

Fama, E. F. and French, K. R. (1992), The cross-section of expected stock returns, Journal of Finance 47(2), 427-65.

Hamilton, J. (1989), A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle, Econometrica 57(2), 357-84.

Dr. Hui Xu, CERF Research Associate, January 2019

Brexit: Investor Paranoia and the Financing Cost of Firms

Financial markets faced a bumpy ride in 2018. The Financial Times report that global bond and equity markets shrank $5tn last year. Two major risks have been disrupting the markets during the past year: US-China trade dispute and Brexit. The two risks, however, are essentially the same: both would cause new frictions and impediments to the existing trade frameworks and unsettle investors’ nerves.

The risks may have consequences on firms’ financing cost for real reasons. Take Brexit with no deal as an example. First, a firm’s revenue can decline due to the friction in the product market, especially for British firms that heavily depend on the European markets. Second, the friction in the labor market may increase a firm’s production cost. Both will lead to adverse effects on a firm’s cash flow and, consequently, the firm’s financing costs. However, the Brexit might also increase the firm’s financing cost just because the investors become paranoid and exaggerate such adverse impacts brought by Brexit.

Yet, to what extent does investor paranoia affect a firm’s financing cost? The question is interesting for two reasons. First, although economists have been assuming investors to be rational, empirical evidence has challenged this view. Answering this question not only contributes to the evidence of irrationality, but also quantifies the real impact of investor irrationality on firms. Second, irrationality drives the valuation from the fundamentals and, de facto, creates possibility for arbitrage.

A work in progress by Frank, a research associate at Cambridge Endowment for Research in Finance (CERF), and his co-authors, studies the question by studying the yield difference of British corporate bonds maturing before and after March 29th, 2019, the date on which Great Britain is set to leave European Union. The idea is simple. Take a corporate bond which matures one day before March 29th and another identical bond which matures one day after March 29th, if the yield of the latter is significantly higher, then we can conclude that the yield difference captures the impact of investor paranoia on the firm’s debt financing cost. Even if Great Britain crashes out of EU without a deal on March 29th, it can hardly affect a firm’s fundamentals, such as revenue and cost, within one day. Therefore, the only explanation for such a yield difference lies in investor paranoia.

Guided by the empirical design, the authors collect a small sample of British corporate bonds. The preliminary analysis does show that bonds maturing after the Brexit date have a higher yield than similar bonds maturing before the date, indicating the real financing cost on firms due to investor paranoia about Brexit risk. The authors are in the process of collecting more data and a working paper and more results will be published very soon.